Nancy and I are just back from

seeing the new “Stieglitz, Steichen,

Stieglitz, Steichen,

November

10, 2010–April 10, 2011

Galleries

for Drawings, Prints, and Photographs, 2nd floor

Stieglitz was the first

photographer ever to have his work at the Met:

in 1928 he donated 22 of his own photographs, and that December he wrote

a letter to the curator of the MFA in

But this show is one that stands out, as it contains

incredible masterpieces from these three, related giants of the history of the

art of photography in

Rather than go on about how wonderful it is, I am instead going to present a series of images of the photographs in the show (that I have shamelessly stolen from the Met’s website about the show and the images from it). I have also included below a review by Karen Rosenberg of the show from yesterday’s New York Times.

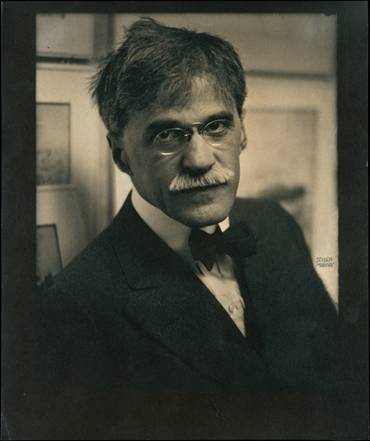

I have included photographs of each of the artists (Steichen’s

photographs of Stieglitz and of himself; Stieglitz’ photograph of

So…enjoy the images, then go see the show! (You also may want to purchase the excellent

catalogue from the show, done by the curator, Malcolm Daniel: Stieglitz,

Steichen, Strand: Masterworks from the

Edward Steichen. Alfred Stieglitz at 291, 1915.

Gum bichromate over platinum print

Edward Steichen. Alfred Stieglitz at 291, 1915.

Gum bichromate over platinum print

Alfred Stieglitz. Music - A Sequence of Ten Cloud

Photographs, No. 1, 1922. Platinum

print

Alfred Stieglitz. Music - A Sequence of Ten Cloud

Photographs, No. 1, 1922. Platinum

print

Alfred Stieglitz. The

Street, Fifth Avenue, 1900–1901, printed 1903–1904. Photogravure

Alfred Stieglitz. The

Street, Fifth Avenue, 1900–1901, printed 1903–1904. Photogravure

Alfred

Stieglitz. From My Window at the

Alfred

Stieglitz. From My Window at the

Alfred

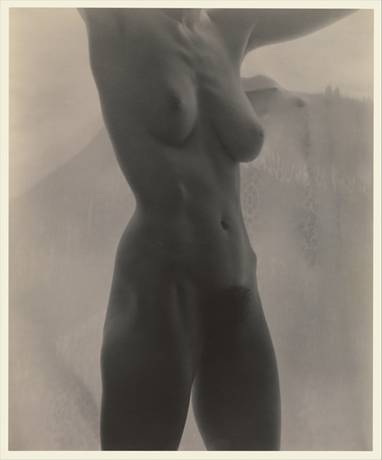

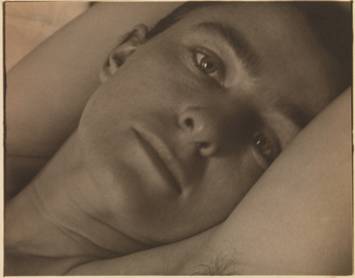

Stieglitz. Georgia O'Keeffe—Torso, 1918. Gelatin silver print

Alfred

Stieglitz. Georgia O'Keeffe—Torso, 1918. Gelatin silver print

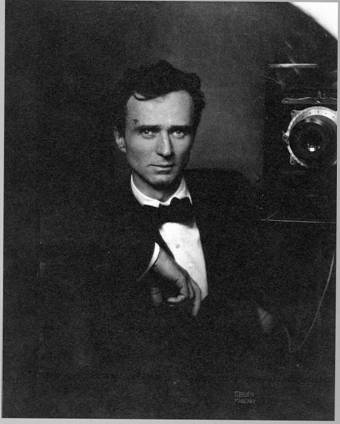

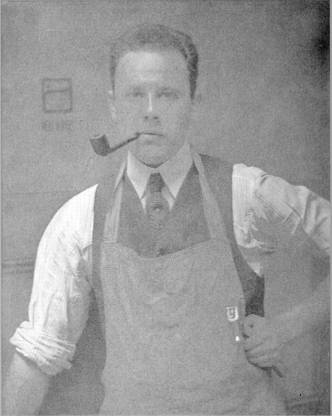

Edward Steichen. Self-portrait,

1917. Platinum print

Edward Steichen. Self-portrait,

1917. Platinum print

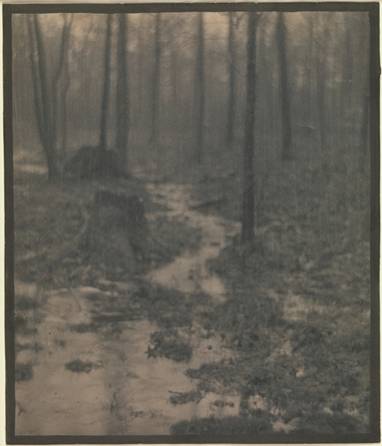

Edward Steichen. Woods

Interior, 1899. Platinum print

Edward Steichen. Woods

Interior, 1899. Platinum print

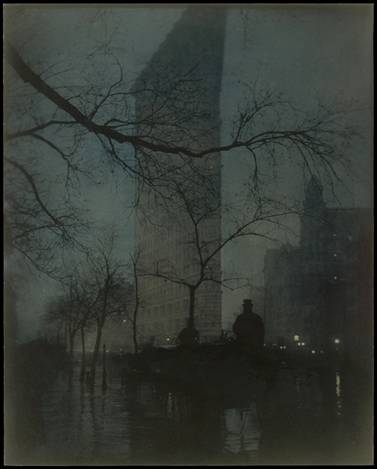

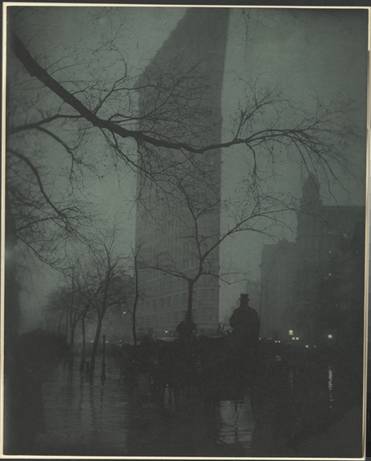

Edward Steichen. The

Flatiron, 1904. Gum bichromate over

platinum print

Edward Steichen. The

Flatiron, 1904. Gum bichromate over

platinum print

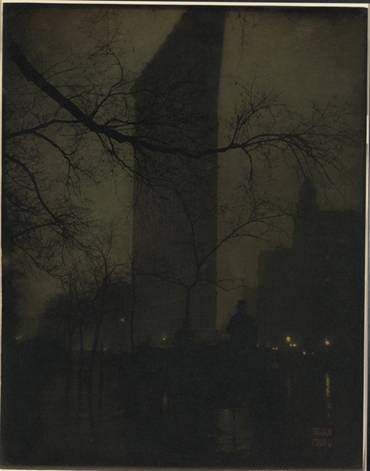

Edward Steichen. The Flatiron, 1904, printed

1909. Gum bichromate over platinum print

Edward Steichen. The Flatiron, 1904, printed

1909. Gum bichromate over platinum print

Edward Steichen. The

Flatiron, 1904, printed 1905. Gum

bichromate over platinum print

Edward Steichen. The

Flatiron, 1904, printed 1905. Gum

bichromate over platinum print

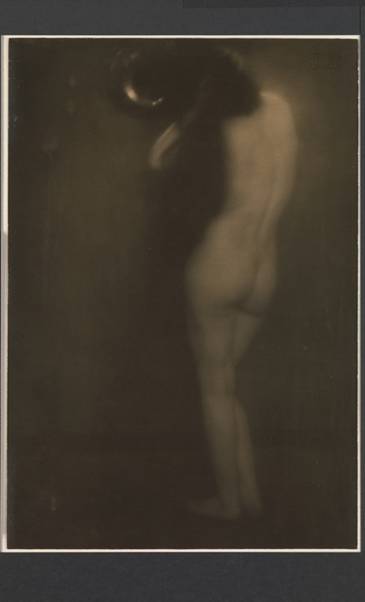

Edward Steichen. The

Little Round Mirror, 1901, printed 1905. Gum bichromate over platinum print

Edward Steichen. The

Little Round Mirror, 1901, printed 1905. Gum bichromate over platinum print

Alfred

Stieglitz. Paul Strand, 1917. Silver-Platinum print

Alfred

Stieglitz. Paul Strand, 1917. Silver-Platinum print

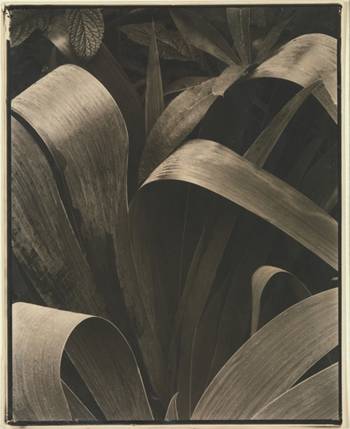

Paul Strand. Garden

Iris—

Paul Strand. Garden

Iris—

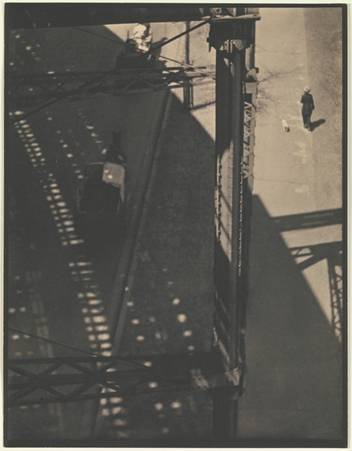

Paul

Strand. From the El, 1915. Platinum

print

Paul

Strand. From the El, 1915. Platinum

print

Paul Strand. Wire Wheel, 1917. Silver-platinum print

Paul Strand. Wire Wheel, 1917. Silver-platinum print

Paul Strand.

Paul Strand.

Art Review

Photography: A Coming-of-Age

Story

By KAREN ROSENBERG

Published:

November 18, 2010

Like other major

American museums, the Metropolitan was slow to recognize photography, but Alfred Stieglitz gave

it a big push in the right direction. In 1928 this Photo-Secession pioneer

donated 22 of his own works to the Met. They were the first photos to enter the

collection.

Paul Strand’s “Geometric

Backyards,

A few years later, in

1933, Stieglitz made a larger gift of more than 400 works by his

contemporaries: Edward Steichen, Paul

Strand, Clarence White, Gertrude Käsebier and many of the other photographers

he had promoted in his New York gallery, 291, and his influential journal,

Camera Work.

The museum’s stunning “Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand,” mostly

drawn from the collection, gives us just the big three — the impresario and his

two greatest photographer discoveries. (Georgia O’Keeffe,

arguably his best find in any medium, appears as a portrait subject.) They were

a contentious group, if you could call them a group at all. Steichen made his

mark in the early years of 291, while

Organized by Malcolm

Daniel, the curator in charge of the Met’s photography department, “Stieglitz,

Steichen,

And though the

pictures come from the collection, the show has an impressive story arc about

photography’s coming of age. The exhibition segues from Steichen’s hazy,

nostalgic Pictorialism to

Stieglitz’s own

transition to a more clean-lined, geometric style is well documented in the

first and largest gallery, with a rich selection of

“Winter,

Nearly three decades

later he photographed the city from on high, looking out the windows of his

30th-floor apartment in the Shelton Hotel and his nearby 17th-floor gallery, An

American Place. Here the metropolis is brisk and orderly, if still a bit

alienating, epitomized by the neat scaffolding of a fast-rising skyscraper in

the distance.

The Met’s show

reaffirms that while Stieglitz was a great photographer, he was an even better

cultivator of talent. In 1900 a 20-year-old named Edward Steichen paid a visit

to Stieglitz on his way to

Although Steichen’s

shadowy nudes and foggy woods shared the fussy look of fin-de-siècle painting,

they were products of state-of-the-art photographic technology. He was a

virtuoso printer, employing as many different techniques and pigments as

necessary to produce the desired pastel-like effect. In the Met’s three large

exhibition prints of “The Flatiron” — the only ones known to exist — Steichen

used a combination of gum bichromate and palladium to envelop the downtown

landmark in Whistleresque mists of indigo and gray.

Back in

Steichen’s flair for

portraiture ensured a steady income stream and some excellent social connections.

After World War I he worked as the chief photographer for Vogue and Vanity

Fair; the Met has a smattering of these images, though its vision of Steichen

is filtered through Stieglitz’s collection.

For the same reason Paul Strand is represented by early

work, which fortunately is superb. Under Stieglitz’s direction he developed a

precise, “brutal” (to use Stieglitz’s word) aesthetic that was in tune with the

radical modernism of the 1913 Armory Show.

The Met has several of

Strand’s humanism —

nurtured early on by his teacher Lewis Hine at the

In 1929

The central dynamic of

“Stieglitz, Steichen,

“Stieglitz, Steichen,

Strand” continues through April 10 at the