New

Delhi Conference, 14-15 November 2014

A BRIEF COMMENT ON WHAT I OMITTED REVIOUSLY: THE UA CONFEENCES IN CHICAGO, SÃO PAULO, AND RIO

URBAN AGE TOUR OF DELHI – 13 NOVEMBER

THURSDAY

THE CONFERENCE: DAY ONE – 14 NOVEMBER FRIDAY

DEUTSCH BANK URBAN AGE AWARD CEREMONY - 14 NOVEMBER FRIDAY

THE CONFERENCE: DAY TWO – 15 NOVEMBER THURSDAY

This year’s Urban Age

conference, Governing

Urban Futures, which took place in New Delhi, 14-15

November, followed the recent pattern of being issue-centered, rather than

being primarily about a particular city or region. The topic, as described by Philipp Rode (Executive Director of LSE

Cities and the Urban Age) and Priya Shankar (Research Office at the program) in their excellent

introductory article, “Governing Cities,

Steering Futures,” for the conference Newspaper,

was examining

the link between urban

governance and our collective capacities to engage with and shape the future

development of cities. By investigating the way we govern urban futures, we analyse how the decisions that are made (or not made) today

have long-term implications reaching well beyond the boundaries of individual

cities – and aim to achieve a better understanding of the underlying conditions

and processes that allow for participatory, effective, accountable and

future-oriented decision-making in and for cities.

These

enquiries take place against a background of some major changes in urban

governance, above all, the trend towards ‘urbanising’

government, alongside the re-scaling of planning functions, both part of the

considerable decentralization efforts occurring in both developing and

developed countries since the 1990s. We also identify a shift towards a broader

coalition of private and civil society actors – replacing traditional hierarchical

coordination of urban development with more networked forms of governance –

while acknowledging the critiques of these shifts and the questions they raise

around the processes of decision-making and democratic legitimacy. The last two

decades have clearly witnessed an increase in the role of the private sector as

a result of economic globalisation, far-reaching privatisation of former state functions, the increasing

importance of partnerships between public and private sectors as well as

greater levels of private capital flowing into urban development, (due not

least to substantial infrastructure funding gaps, recently exacerbated by

severe public budget constraints in some regions of the world). We also recognise that, (well before recent trends of ‘networked’

governance emerged), there have always been urban areas and aspects of urban

life in several parts of the world that the state has never fully reached or

formally governed.

…four key trends and themes emerge for what will be critical

in shaping our urban futures. [1] Globalisation,

particularly economic globalization through the links of trade and the flows of

capital and investment, is affecting cities throughout the world. [2]Technological

change, especially the revolution in IT, is changing the nature of all

human interactions but also of state-society relations. [3] There is increasing

inequality in most cities and

increasing informality in many. And [4]

all cities are confronting the existential threats presented by climate change. Each of these trends

has significant implications for the governance of cities. At the same time,

urban governments face fundamental choices about how to respond to these

trends, and what is decided now will be critical in steering both urban and

global futures. [numbering

and emphases added]

The

conference Newspaper

is available online, and I recommend it to

you most highly. It is full of extremely

informative articles, written mostly by those who presented at the

Conference. (Wherever I quote something

without specific attribution, it will be from this publication.)

For those

of you who are not familiar with it, the Urban Age

is a program housed within the LSE

Cities Program;

it has mounted a series of world-wide conferences, dedicated to studying the

problems and issues facing cities in the 21st century and creating

dialogues designed to find solutions. (See the UA’s own very informative

website: www.lsecities.net/ua/).

100 years ago, 10% of the world’s population lived in cities, while 90% lived

in rural areas. The Urban Age program began at the moment in history when the

world crossed the point that more than 50% of its population lived in

cities—and the United Nations predicts that by 2050 approximately 75% of the

world will live in cities. This fact means that the nature of cities will have

an incredibly important impact on the nature of life on this planet. The Urban

Age program is centered at the London

School of Economics, and funded by the Alfred Herrhausen

Society (the international forum of Deutsche Bank). These conferences

are designed to form the framework for the development of an ongoing dialogue

between government leaders, academic experts, and urban practitioners—it brings

together a diverse assortment of architects, city planners, civil engineers,

government officials, transportation experts, real estate developers,

academics, and various others who study these areas (some as unlikely as a

psychoanalyst like me), who importantly talk with each other across disciplines

in a way that rarely happens at other times.

At their outset, the Urban Age ran a series of conferences

which explored the urban natures and futures of individual cities. The The Endless City (Phaidon Press, 2008) is a book published by the Urban Age that presents the integration of the

findings from this first group of conferences which began in New York (q.v., my

write up) in

February 2005 and which culminated in Berlin in November 2006 (with Shanghai,

London,

Johannesburg,

and Mexico City

in between). It was co-authored by Ricky

Burdett (one of the Founders of the Urban Age and Director of the LSE

Cities Program) and Deyan Sudjic (member of the Urban Age team and author of The Edifice Complex: How the Rich and

Powerful--and Their Architects--Shape the World, and many other books).

After this initial group, there was a second series of

conferences focused on the broader regional contexts of that began in November

2007: the first was in Mumbai (q.v., my

write up),

followed by São Paulo,

and, in 2009, Istanbul (q.v., my

write up),

which was the final of the three meetings of this second group. Living in the Endless City,

also co-authored by Ricky Burdett

and Deyan Sudjic and

published by Phaidon Press (2011), presents an

in-depth overview of the findings from this series of conferences.

Over

the last four years, the Urban Age conferences

then focused on key thematic areas of urban change: the global shifts of urban

economies (Global Metro Summit in Chicago,

2010, organized by LSE Cities in

conjunction with the Brookings

Institution Metro Policy Program); health and wellbeing (Cities, Helath, and Wellbeing, Hong Kong in

2011 [q.v., my write up]); environmental sustainability and

technology (The Electric

City, London in 2011

[q.v., my write up]; the online version is in need of repair, but the text is mostly

intact, albeit the illustrations are completely missing]); and the physical

transformation of cities (City Transformations, in São

Paulo, 2013).

A BRIEF COMMENT ON

WHAT I OMITTED PREVIOUSLY:

THE UA CONFERENCES IN

CHICAGO, SÃO PAULO, AND RIO

There have been 13 conferences, and I have attended 9 for

them—including the first and the last 8. Of those I have attended, there were

only three that I did not write up; and

in all three cases it was because there were important things that angered me

about them that I did not choose to write about…but I am now moved to mention

them here.

In Chicago, I

was deeply bothered by the line at that time taken by the Brookings Institution people who co-led to conference: they seem

subsequently to have changed their tune, but at that point they were focusing

exclusively on action on the local level and emphasizing the need for focusing

on involving private partners and sources of funding for public programs—which,

albeit arguably needed in the face of the diminished availability of public

funding in the world, was dangerously ignoring the shortcomings of this

approach (viz., the danger of blindly

relying that the interests of the public adequately would be represented and

protected in the process, and the implicit justification of the abdication of

responsibility by government —and particularly at the State and Federal

levels—to fund those areas which simply cannot

be financed in any way other than by

government [e.g., those

infrastructure and other long term projects where the ROI (Return On Capital)

is not immediately capture-able, or is so long range or small as to not provide

adequate incentive for private investment of capital]). I am a great believer in the importance of

action on the local level: in fact, I sometimes am moved to say that the only meaningful action is local; and

that if things are not made meaningful on the local, community level, they will

not be meaningful at all. (And, of

course, remember that I am a psychoanalyst: I am someone who is profoundly

convinced that the very most

meaningful changes take place on the personal, individual level!)

Nevertheless, there are ways that too exclusive a focus on the local can

be used to distort and hide societal problems, and to avoid more official

societal responsibilities. There are

people who rather venally use such an exaggerated emphasis to very selfish and

bad ends; and there are others who are just so naively swept up in such

approaches that they miss the inherent dangers and shortcomings. One way or the other, it is a bad mistake.

In the case of São

Paulo and Rio, my reluctance to

write about the conferences was due to my general discomfort and anger at what

dealing with issues in Brazil is like: I have experienced an enormous tendency

there to operate in a way that seems completely to believe positions that are

desired to be true but simply are blatantly false. I believe this tendency arises from what I

consider to be the underlying falsehood of Brazilian society: “We have a fully

racially integrated society in Brazil.

Race is not a problem here.” This

seems firmly believed, and totally false: Brazilians have 47 distinct words to distinguish different levels of darkness of

skin color, and, in their society, social economic level correlates completely

with level of darkness of skin. If one

is interested, Michael Kimmelman, a wonderful member of the Urban Age

International team (and the best

writer on architecture the Times has had in decades), did an

excellent article in the New York Times on 25

November 2013 after attending the Rio conference about what Brazil was really

up to in how it was dealing with the World Cup and 2016 Olympics: ”A Divided Rio de Janeiro, Overreaching for the World”.

He and I spent a great deal of time together on the tour and at the conference

in Rio discussing some of this; and while I am more extreme in my feelings

about this than he, he obviously shares some of the same perspective. He wrote,

Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, is

saying all the right things about combating sprawl, beefing up mass transit,

constructing new schools, and pacifying and integrating the favelas, where one

in five city residents lives, with the rest of the city.

But as months of street protests illustrate, progressive

ideals run up against age-old, intractable problems in this city where class

difference and corruption are nearly as immovable as the mountains. This is a

city divided on itself.

The

article offers an important critique of

what Brazil is actually doing in these efforts in contrast to what they claim

to be doing, and I highly recommend it to you.

URBAN AGE TOUR OF DELHI – 13 NOVEMBER

THURSDAY

Our tour was led by Jagan Shah (Director, National

Institute of Urban Affairs). [The photographs in this section are my own,

except for the one below, which is from the Conference, and is by Catarina Heeckt.]

Jagan said it was hard to say how many actually live

in Delhi: 13 million, although many say 16 million; but after Partition it was

only 2-3 million. Before the 1962 Delhi

Master Plan (done with the help of the Ford Foundation), refugees were

dealt with only on an ad hoc

basis. Inside the Ring Road, which was one of the first creations of the Master Plan,

one still can see the pre-1950s small shops and small plots of land; outside,

the development of the 60s and later takes on a very different urban form. There has been a decision in Delhi to release

the FSI (Floor Surface Index, used interchangeably in

India with FAR, Floor Area Ratio; essentially the gross floor area of all

buildings on a lot divided by the area of the lot itself) almost completely

along the transit-oriented corridors of the city—and there are now buildings of

22 stories going up (most of Delhi is 4-5 stories). There is a new Metro line

being put in along the Ring Road, and an expansion of the retail area, with

permission being granted to convert residential buildings to commercial along

the arteries. We passed the Defense Colony, said to be the most

expensive real estate in Delhi.

At the Moolchand Clover Leaf we turned right on the road that has the remains of

Delhi’s recent experiment with BRT (Bus Rapid Transit). This initial phased was planned to begin with

a 14 km stretch here; but it was shortened to 5 km. What’s more, it is one of the worst designed BRT attempts I have ever seen: the

“dedicated lanes” and stations are in the middle of a major thoroughfare, and

there is no provision for pedestrian access to the stations, which often

requires the perilous crossing of three or four lanes of uncontrolled traffic

flow to reach them (making the stations all but totally unusable); and, shortly

after the system was built, car and truck traffic was granted access to the

“dedicated lanes” which were supposed to be exclusively for the BRT vehicles

alone (thus rendering the system completely dysfunctional). It was a system

that I believe was planned to fail—and fail it did: “people” (and we can only

imagine what constituency comprised this group) demanded the system be stopped,

and no more of its planned 330 km were ever built. The area also has its share of single lane

flyovers—a piece of road engineering so poorly conceived that I have never seen

it anywhere else—which also confound traffic flow on the overcrowded

thoroughfare. (There is congestion automatically created entering and exiting

these flyovers, so that at the best of times they retard rather than assist

traffic flow; and any disabled car on one brings the flow to an immediate and

total standstill, as there is no way to get past it—or to get to it with an

emergency vehicle.) Along this route are

found some of Delhi’s tony gated communities—and less fancy middle class

communities that have erected unofficial gates, aspiring to being a gated

community without any official standing to do so.

We got off the bus at Nehru Place, a bustling collection of buildings that functions as a

prime commercial space which is the biggest “gray” market for electronic goods

(selling and repairing unauthorized copies of electronics equipment and

media—of “questionable” legality):

In the early 80s, this government sponsored

development was unanimously condemned as being “heartless modernism”; and,

indeed, the architecture itself is actually a rather dreadful replica of a 60s

housing complex. Jose Castillo and Richard

Sennett and I were discussing what the residential/commercial mix was; and

I asked Jagan,

who told me that in fact it was built as a 100% commercial complex—that every

unit housed some form of commercial enterprise. This surprised all of us, and

we continued to feel that area distinctly looked as though there were people

living in some of the units. I asked

again, and was told that in fact there were

people who lived in the offices, stores, and shops; but that they were not the

owners, but rather employees of the owners who were often allowed to live in

the commercial space in return for being paid woefully minimal wages (the

difficulties of lower income people finding housing being what they are here).

This mix actually made sense of the “feel” of the place, which had actually

originally led the three of us to assume incorrectly that this was primarily a

residential, mixed use place. But Nehru Place is a locus of enormous life

and vitality—social as well as commercial:

In many ways, it felt like a combination of a

modern electronics market and a souk—a Middle Eastern bazaar: full of energy

and commercial activity, and very much a place of the people. The first two

levels had intense lines of open shops of varying types, all bustling with

activity,

while the upper stories

were given over to individual stores, workshops, and other business

establishments.

We then got back on the buses and drove to

the “slum” of Gavindpuri

we were going to visit. Ahead of us on the road we saw in the distance, through

the haze of Delhi’s intensely polluted air, a mountain rising in a far-off area

of the city. Jagan informed us that this was

one of the many “mountains” of garbage where the cities piles up it waste. The

sheer magnitude of this single pile was frightening. Garbage is an enormous

problem in Delhi (as it is all over India). Power companies and the government

have acquired parts of the Jahanpanah Forest

(the remains of what was a green belt in Delhi), and areas of it have been

given over to garbage disposal. Apparently, another problem is that this

society which is so traditionally respectful of animal life—and of cows, in

particular—actually allows for rather cruel passive treatment of these animals:

particularly after cows cease to produce milk, they are often abandoned without

care or feeding, and they are actually allowed either to starve or die a

painful death from ingesting the plastic that is contained in the garbage they

forage in for sustenance. (This was an uncomfortably shocking revelation to

many of us.)

We got out of the buses and walked through

the streets of Gavindpuri.

This area is a bustling place, full of

people, businesses, and dwellings:

It is obviously informally constructed, often

of substantial materials—but with some very questionable engineering (one of

the issue in Delhi is that it is estimated that over 50% of its built

environment could not withstand even a moderate earthquake):

Here a photograph of a women selling produce

that I include more for its beautiful resonance of the vibrant colors than for

any other reason:

Our destination was the Katha Lab School, a privately funded school for the children of the

community that is also a center for community activities (healthcare, Women’s

Center, etc.). The underlying philosophy is to create change

through the children—directly via education, but also via family involvement.

It is a mixed community (approximately half Muslim and half Hindu), and the

school population reflects that mix. Many of the families at the schools are

migrants who have come to Delhi largely for

the educational opportunities, which are lacking and dysfunctional in rural

areas.

The school’s building is a very modern,

well-designed structure (note the architecturally interesting and functional ramps

on the roof of the complex, using solar energy (note the solar panels on the

right):

The school is supported totally by

philanthropy: e.g., the modern

computer lab was funded by the Prince Charles Foundation. We were told that all

philanthropy in India is directed solely at education and religious institutions,

and never cultural or scientific ones.

We then divided into groups of 8 people, and

parents (all women) of children at the school led the groups on intimate tours

of their neighborhoods. We were led through the narrow pathways through the

community (below you see Sophie Body-Gendrot n the foreground, and

the back of Enrique Peñalosa

in the background):

The dwellings house multiple families in

each. The women have a much higher rate

of employment than men. The men, when they work, are usually employed in

factories or small workshops; but alcoholism and unemployment is rampant. The women are mostly employed as domestic

help (in some of the slightly more affluent apartments adjoining the slum),

working 27 days/month, and being paid INR500 for each “task” they perform (i.e., they will typically work for about

4 different families, and get paid that amount by each—thus getting

INR2000/month [~$33/month] working full days, all but three days a month). The gender distinctions in the employment

situation reminded me of what I had just learned about life in rural India from

a person who runs an outreach political organizing program on the outskirts of

Indian cities: according to whom, typically it is the woman who is the one who

works in rural India, and the husband often sits around drinking tea (or

alcohol, paid for by his wife) all day—and too often beating his wife at the

end of the day. (As an important aside,

I came away from my experiences of this visit to India—in Delhi, as well as in

Ahmedabad, Udaipur, Ranakpur, and Jodhpur—being

convinced that the positive hope for India’s future lies with heavily its

women: they are the ones in the poorer communities who seem to have the potential

for political organization [and they are successfully being organized and

becoming politically important forces in many areas, especially rurally], and

they are already a clear force for change in India’s cities. The women of India are one of the country’s

most valuable, exciting resources.)

Below you can see (on this rather wider passageway), the open sewage

lines that line many of the streets (much more problematic on the narrower

ones):

Some of the passageways are actually given

over entirely to other functions:

Our guide

told us that these open sewers carried only waste water, although there

seemed to be clear elements of fecal waste mixed in. When we pointed this out

to her, she said that wasn’t true because none of the dwellings in this slum

had toilets—although we actually were able to see evidence of some, including

even some PVC drainage pipes on the exteriors of some of the buildings. Gerry Frug commented that this is one of the problems with

the “interview method” of research: you ask a question, you get an answer; but

then it is not clear what the answer in fact means. (I added that it also makes

one aware that one may, in retrospect, not even understand what one’s question meant.)

We then re-boarded the buses and drove across

the Yamuna River (and its beds of

water hyacinth) to Noida (the city

developed by NOIDA, the New Okhla

Industrial Development Authority), actually in the state of Uttar Pradesh,

which is a second generation piece of urbanization, all high-rise (there is a

planned 60 story tower being built), a community of significant wealth (the

highest per capita income of the entire capital region). It is a center for outsourcing IT, software

companies, power utilities, automobile industry, and film and television

industry. There are also extensive

shopping malls and arcades in the district. Many of its residences are owned as

second or third homes for the wealthy (some simply as investment properties for

the rich), and many are sparsely-occupied.

We got off the buses at the NOIDA Metro

station, a new, modern structure, amidst the bustle of a small local market:

From here we boarded the Metro. This is a rather impressive transportation system, with high

speed, quiet, comfortable cars and efficient, clean stations. The system’s five

current lines have 193km of tracks, some elevated, some underground serving 141

stations (38 of which are underground).

The system was largely financed by Japanese

investment—in return for which Japanese companies (largely Mitsubishi) were

given the contracts for making the equipment and rolling stock. It is

considered to be very successful, with a daily ridership of 2.4 million. Plans for the expansion of the system are in

place, and two new lines and several extensions of existing lines are already

under construction. (Below is a photo taken from the Metro of new construction.)

In minutes, we arrived at Connaught Place. Officially named Rajiv Chowk, Connaught Place (or CP, as it is often called) is

one of the largest financial, commercial, and business centers in New Delhi.

Formerly the headquarters of the British Raj, it was planned and developed by Edwin Lutyens.

At the intersection of several important thoroughfares—and with its

proliferation of shops, trendy bars and restaurants (the Urban Age welcoming reception was held in the rooftop open area of

one such bar/restaurant, immediately following the tour), movie theaters, and

its central park area (a gathering place and location for many events) in the

middle of its concentric encircling roads—Connaught

Place has become one of the hot gathering places for young people in India.

THE CONFERENCE: DAY ONE – 14 NOVEMBER FRIDAY

Morning Session

[N.B.: The presentations and panels from the

conference are all available for you to watch yourself on the Urban Age YouTube Channel at http://delhi2014.lsecities.net/video/;

the slides from each

presentation that had them are available

at the same place. I shall not specifically remind you that

these are available, except in the case of the video that includes our friend Charles Correa, which I suggest you

watch to get a sense of the power and elegance of Charles and his thinking. His brief talk

begins at minute 31:30 of video of his panel available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=dloCPkws8i8&t=26m15s.]

{I have set off in these bold curved brackets {} any personal commentary I have

inserted about any of these talks during the conference.}

The

first day’s opening remarks began with a welcome from Anshu Jain (Co-CEO of Deutsche

Bank, pictured below [all conference photographs are by Catarina Heeckt]).

Anshu Jain spoke about Alfred

Herrhausen and the Society founded in honor of his great work. He noted that the

Conference was being co-sponsored by the National

Institute of Urban Affairs in New Delhi, and thanked its Director, Jagan Shah.

He said that he had been fortunate to live in many great cities, and had

found that while each was unique, all great cities had some important things in

common: they were “multicultural, a

crossroads of different nationalities, languages, faiths, traditions, and human

stories.” People from diverse backgrounds, coming together and creating a

collective identity; and he quoted Jane Jacobs, “The metropolis provides what

otherwise could be given only by travel.”

He spoke about the fact that urbanization was one of the defining issues

of modern life, with 4 billion people—54% of the world’s population—currently

living in cities. In the middle of the

last century, 2/3 of the world’s population was rural; by the middle of this

century, 2/3 will live in cities—meaning the urban population will be what the

entire population of the world is today.

He noted that India alone is predicted to have a rise of 400 million

people living in its cities by 2050.

Today cities occupy 2% of the world’s land area, but account for 80% of

global wealth. 1/3 of the increase in

the world’s economy is predicted to occur in its cities—and that today in China

and India, the average income of city dwellers is three times that of its rural

people. He discussed the fact that there

were downsides of urbanization: urban concentrations place a stress on water,

power, sanitation, and transport—all of which need to be managed. He raised the

specter of the effects of outbreaks of infectious diseases in the densely

populated cities in the world.

Urbanization has not brought prosperity for all: worldwide, 1 billion

people (1/7 of the world population) live in slums, and that number will double

by 2030. Urbanization will happen, he said; the question is whether it will be

a force for good. China and the Eurozone

will be generating excess savings of ~$3 trillion; these savings will seek

solid, predictable investment. Simultaneously, successful urbanization will

require huge resources and major long term financial investment—and financial

institutions have a crucial role and an enormous responsibility in converting

these savings into capital that can be utilized for our cities to develop. Governing urban futures and the choices we

make now are going to influence so many lives in the future; and we at Deutsche Bank and the Alfred Herrhausen

Society are delighted to contribute to and to participate in this Urban Age

conference, and the bringing together of so many experts to discuss these

crucial issues.

Craig Calhoun (President and

Director of the London School of

Economics, pictured above with Anshu Jain) thanked Anshu Jain and the Herrhausen Society, offered his welcome, and noted the

long and important connections between the LSE

and India. Craig noted the 100 Smart

Cities Initiative in India that Anshu had mentioned,

and its relation to the work done at the Urban

Age Electric City conference we had in London two years ago. Here in Delhi we will discuss key questions

of governance: interrelated themes of decentralization, accountability,

partnership, land governance, and infrastructure. There would be many interconnected issues we

would be examining: decentralization, land use, governance, and infrastructure

among them. We will try to compare

different perspectives on agendas of urban change from the experts we have

gathered, not only from India but from over 20 cities on five continents. Craig noted that it had taken London

100 years to grow from 1 to 10 million people, which is

1/10 the rate of growth that is taking place in India. We very much need to know how cities are

parts of larger developing trends; and it is this which will enable us, in the

phrase that guides us in this conference, “to govern our urban futures.”

INAUGURAL ADDRESS:

Greg Clark

(Minister for Universities, Science and Cities for the UK Government) gave the opening keynote

address.

He

mentioned that the LSE mascot was the beaver—an odd choice, save for the fact

that it is an animal known for being an industrious, social creature; and noted

that cities bring people together in collaborative ventures of complexity and

specialization that are profoundly related to economic growth, even at a time

like the present when electronic media actually make it possible for people to

live in isolation from others. There has

been a tendency to centralize in the UK, with London having been the main,

prospering center of growth; but there is now a move to create other centers of

growth—using the two very different cities of Manchester and Liverpool as

examples—and the move towards prosperous networks of cities. Greg

said there were important lessons that need to be learned: we must recognize

the differences between cities (their specific histories, characters, and

feels); we have to respect the past and history, but not be imprisoned by it;

boundaries need to be thought about carefully (cities often outstrip their

municipal borders, which often reflect neither economic reality nor geography);

connectivity and transportation are key issues in successful urbanization;

education is of crucial importance in the process.

Ricky Burdett (one of the Founders

of the Urban

Age and Director of the LSE

Cities Program, and the dear friend who originally brought me

into the Urban Age program; pictured below)

gave an overview in which

he said that we are here to hold up a mirror to what exists—to share

perspectives, not to tell people what the solutions are for their cities. Ricky

summarized some of the research the program had been doing on Delhi (actually

informed by the work of the past 10 years of the Urban Age program), and as

presented in the conference Newspaper: a collection

of essays (one group from a global perspective, one about India, and the third

from the perspective of other parts of the world) plus a data section. The speed of urbanization is staggering, but

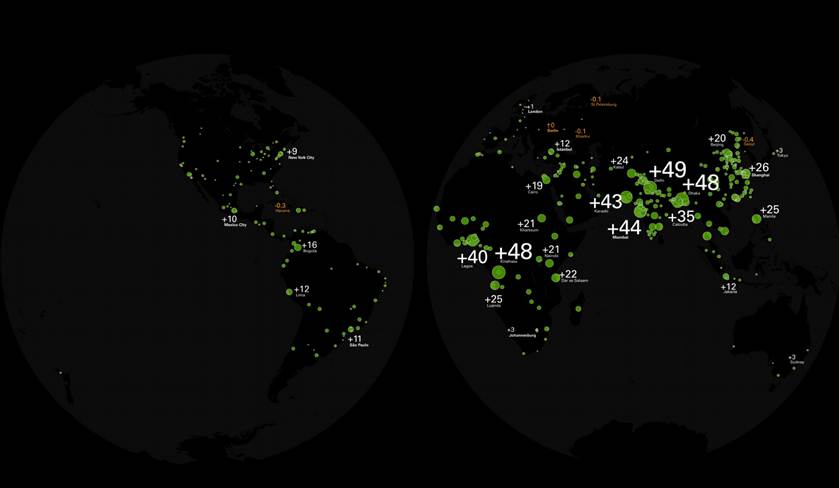

uneven across the world: NY is growing

at 9 people/hour, London at 1/hour; and Lagos is growing at 48 people/hour—and

Tokyo, the world’s largest urban population, is predicted to go into a negative

growth rate over the course of the next year, along with some Russian and

American cities. These facts are graphically

presented on the map below. [I am using Ricky’s presentation to make you aware

just how much wonderful information is available in the slides that accompanied

many of the talks. To make the point, I

am showing a large number of his slides, which I shall not do with the other

presentations. But be aware that the slides from other

presentations are available online at http://delhi2014.lsecities.net/video/.]

But

one thing we know, unless we talk about governance, we haven’t done

anything. How a city is governed—and

what the boundaries of that city are—is absolutely fundamental: some areas of

city authority (where they say “mayor” has control; indicated in the darker

colored sections) are relatively small in comparison their much larger functional

regions (e.g., São Paulo and New York

below);

while in a city like Istanbul, the mayor

has a vast area under his control, virtually 100% of the functional region of

Istanbul (q.v., below).

Whereas

London was purposely reinvented to have a closer fit between its city authority

and its real boundaries, cities vary widely on this: in Delhi, 66% of the

population lives within the city’s municipal boundaries, whereas in Paris it is

only 18%, and in London and New York fit is about the same at 39%). The graph below presents some of the data on

Delhi compared to other cities.

Economically,

the predicted growth rate

(2012-2030) in GVA (Gross Value Added)

in Delhi is 7% (compared with 2.8% in London and 1.1% in Tokyo); the GINI

coefficient (a measure of income distribution where the higher number

represents greater inequality) is a whopping .60 in Delhi, whereas in Berlin it

is only .29. The rest of the graph

(presented below) presents other aspects of comparison:

Delhi’s

air pollution is extremely high (289 PM10 levels [pg/m3]),

compared to London at 22. It is also

worth noting that while Delhi’s built environment is essentially 4-6 stories

high, it is nearly twice as dense as Tokyo.

Ricky pointed out that

there are different patterns of built environment (Hong Kong has gone vertical

and Mexico City doesn’t end, q.v.,

below);

different forms of governance

(in London there is no state government to contend with—all city and national;

in Delhi, it is largely a question of state government); and the patterns have

a very significant effect on the environment and on social cohesion. To use London as an example, below is a

representation of the distribution of wealth, showing in dark red are where

people are most deprived (lower levels of education, higher unemployment,

teenaged pregnancies, etc.) and in

green, exactly the opposite (higher education, longer life expectancy lower

levels of unemployment, etc.)

Every

city will have this map. This is an

unequal distribution; it is about inequality.

And here is Ricky’s “analytic, social scientific analysis of London,”

which is actually what London “feels” like:

How do we try to

avoid this inequality happening? Forms

of governance and control matter.

Compare what we were able to institute in recent years in London (where

there had been almost no local representation) with the situation in Delhi:

What you do not see

on the London chart is the orange color between the blue of the central

government and the green of the local authorities, which is the state; in Delhi

there is a lot of orange, a lot of blue, but not very

much green, local control. What is

missing in Delhi is the red of metropolitan governance which was what we were

able to create in a major way in London beginning with Ken Livingston.

The two biggest

issues that cities face are the environment and social cohesion. On the graph below, the vertical axis shows

the ecological footprint (the further up you go the more energy per person you

use), while the horizontal axis shows the UN Human Welfare index (the further

to the right, the better educated, longer life expectancy, etc.):

The relationship

between human development and ecological footprint has different patterns: The

US is extreme in terms of both environmental and consumption patterns—and the

Earth is in terrible trouble if everyone tries to emulate this pattern. If you look at the dotted line, which is 1

Earth’s amount of energy we have, you see that if we all live like Americans,

we would need 5 Earths—which simply

won’t work! India is way down at the

bottom at the moment—and this is a big transition, a fascinating moment; and

the question is which way does it go?; which model do

you choose? And we at the Urban Age and

the LSE are asking how does governance actually help us to understand these

questions?

Shaping

Urban Futures. (Chair: Ricky

Burdett)

Joan Clos (Executive Director,

UN Habitat and Under-Secretary General of the

UN, and former Mayor of Barcelona,

pictured below) gave a presentation entitled, “Towards a Global Agenda for Urban Development,” in which he

discussed how urbanization in the world is going.

In

his important article by the same name in the conference Newspaper, he wrote about the

UN’s New Urban Agenda:

The year

2016 – with the celebration of the third United Nations Conference on Housing

and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) – should represent a turning

point in the debate on the future of our cities. Habitat III is a unique

opportunity for governments and institutions around the world to engage in a

New Urban Agenda that addresses the challenges of rapid urban growth and offers

a new model of urbanisation.

In

tackling the problem of sustainable urbanisation, a

three-pronged approach is needed, covering the areas of urban regulations,

urban planning and urban finance. If the world’s cities are to move from an

unsustainable to a sustainable urban future, it is essential to identify and to

coordinate efficient and implementable measures in each of those three areas.

…Governance

is the enabling environment that requires adequate legal frameworks, efficient

political, managerial and administrative processes, as well as mechanisms,

guidelines and tools to enable the local government to respond to the needs of

the citizen. Local governments have the proximity to translate the principles

of good urban governance into effectively managing, governing and developing a

city, and ensuring equitable access to citizenship…

…Good

governance and the rule of law at the national and subnational levels are

essential for the achievement of those objectives, in order for us to move to a

more sustainable model of urbanisation. If urbanisation is to be truly inclusive and sustainable,

participatory mechanisms and integrated human settlement planning and

management practices are crucial.

He

focused on giving a bit of perspective on where we are and where we are

heading, because we need a new paradigm—if we continue to build cities as we

are now (remember the last slide of Ricky’s), we’re on the wrong track. Joan

said there have been two real revolutions in organizational paradigm: the first being the 19th

century, industrial city, which was transformed by industrialization; because

of the inflow of workers (and immigration) cities demolished and broke through

their Medieval walls and did a huge expansion (he used two cute examples:

Amsterdam in the 1876 and New Amsterdam [Manhattan] in the 1811, which, in the

case of the latter, led to the breaking down the walled city [at Wall Street]

and three surveyors drew the lines of the larger grid which we walk today in

Manhattan); this revolution in paradigm

was driven by the fact that the cities were too crowded: conditions in mid-19th

century London were shocking, with poor people so packed together that it was

the set up for the cholera epidemic of 1851—and the fear which that engendered

led to the walls coming down and the population spreading out. (But Joan pointed out that what made the

change possible was that the rich

people had been packed in with the poor people and were also in danger from

these conditions; and they had the wherewithal to insist that the city spread

out and create room for them to isolate themselves.) Vienna and Barcelona grew similarly at that

time. In this expansion model there was

no zoning, no legal prescription for how to use the land. The

next revolution was 20th century model was the new paradigm

developed by Le Corbusier in the 1971: the utopian city of the future for 3

million people. This model of

towers-in-the-park, superblock, with wide streets, and the car was so

successful that it has been built all over the world—and it is continuing to be

the model for building all over the world, even where it no longer makes sense. From the socialist perspective, it satisfied

the push for every industrial worker to have the same decent apartment, equal

for every worker. And every industrial

worker will have a car—the technology of the moment, which would allow freedom

of movement. Joan showed just the towers-in-the-park

side of a slide we often show in the Urban Age, and asked whether the audience

who do not know it from the Urban Age could identify where the very

generic-looking development might be in the world—Asia, America, Africa? Is it

possible to differentiate?

It

is impossible to tell, because it has been reproduced everywhere. In case you are

not familiar with the whole photograph, it is of Caracas:

It

is an ecologically unsustainable model; it consumes a huge amount of energy.

He

said what is needed is a change of paradigm, a new, 21st century

model. The old model consumes too much

energy and has led to a suburbanization of housing. We need a model using infrastructure needs as

the guide for planning. The UN is trying

to gather people together to work out a new paradigm.

Ricky asked whether Joan

thought a change of government structure could help in the creation of this new

model.

Joan: Of course, because

every one of these changes of paradigm has come with a change of

government. He noted that the 20th

century model had been corrupted by both sides in the Cold War: the Soviet and

capitalistic patterns both follow the same model of Le Corbusier. But we shall have to see what happens with

democracy over the coming years.

Richard Sennett (the other

co-Founder of the Urban Age, and

Professor of Sociology at the LSE

and NYU, pictured below)

gave a talk, “Ungovernable Urban Complexity,” in which he raised the question of

how urban designers can have things that may be useful in Delhi. Richard

began by quoting Erik Erikson in his biography of Gandhi: “Growth means

managing complexity that you don’t simplify.” His premise is that cities

generate complexity, and that the increasing speed of change requires new forms

of thinking and new forms of management: historically there was a more natural

fit between form and function, but that has broken down, and the fit now must

be managed. The speed of growth tends to

produce a tendency to produce an artificially tight fit between form and

function that causes problems and mis-matches.

Technology must be managed and adjusted toward how people actually live; there

is a real question how to use technology democratically. Climate change underscores the need to think

about issues in broader and non-linear terms.

As Richard wrote in his

article, “Coping with Disorder,”

The

perils of climate change cannot be addressed by thinking at the scale of urban

self-shaping, as Max Weber wanted; or that of local, inclusive democracy, such

as Henri Lefebvre believed in. And climate change has rendered Franz Fanon’s

opposition of urban versus rural out of date.

Adapting

to climate change…means that coherence of the city’s form will alter, due to

forces beyond human control.

“Unpredictable”

is the key word – there is certainly a water crisis coming, but we don’t yet

know what form it will take. Almost all models of climate change argue for

non-linear changes, chance combinations, erratic consequences, all occurring in

the coming decades. All this argues that rural and urban must be seen together,

as one disturbed ecology. The political problem is how

to practice governance under these conditions. In part, the needs of the city

have to dictate what happens in the countryside, but the political problem is

complex because the natural system is becoming ever more unstable. How do you

legislate under these conditions?

To adapt,

the city can no longer cohere; we must meet the uncertainty of a physically

unsettled world by thinking of the city itself as a more unstable place.

This is

the logic of what natural scientists call open systems. These are structures

which model chance, or seemingly illogical change, or complex events which de-stabilise an equilibrium condition.

All these

phenomena are erratic in the short term, year-on-year, though the long-term

effects are certain over the course of decades. We should be thinking about the

networks linking big cities in the same way. Specific patterns of migration are

as unstable in the immediate term as changes in the natural environment; for

example, movement across the Mexican-American border is an erratic, convulsive

process year-on-year, though the cumulative effect is clear. So, too, is the

economy of networked cities – financial flows are not smooth and linear, nor

are investments in real estate or primary industry. Open system analysis thinks

about networks as trembling rather than placid connections – because the

connections are complex they are peculiarly open to disruption.

We must

acknowledge the disorder to come and learn to cope with it: the urban challenge

we face now is how to live openly.

Democratic

politics have to find a way to manage the radical unfolding of change—and this

is a problem of governance. It is the Eriksonian idea of coping with rather than trying to defeat

complexity. Governance is about how to manage conditions—the effects of nature,

real world problems.

Joan Clos raised the question

of who it is who is going to be providing it? Will it be the highly skilled

majority, or the majority with low levels of skill and knowledge?

Richard said that in open

systems theory “chaos” does not mean lack of form; it refers rather to the

irregularity of events.

Ed Gaeser (Professor of

Economics at Harvard University,

below) spoke of “City Institutions for

an Urban Age.”

He

began by disagreeing with Gandhi’s statement that, “I regard the growth of

cities as an evil thing, unfortunate for mankind and the world.” While they are capable of breeding evil, Glaeser believes

that they actually are engines of progress:

in fact, “the pathway out of povery is through

urbanization.” He cited the fact that

before 1960, the poor were 0% urbanized; since then there has been a 10% growth

of urbanization and a 50% increase in income.

In rich countries there is little difference in reported happiness

levels between urban and rural dwellers; in poor countries, rural dwellers are

far less happy than their urban counterparts (with the interesting exceptions

of Iraq and Bangkok). People in cities need government, and there is real

impact to the decisions made by government:

before the huge expenditures NYC made for public health (mainly to

provide clean water), life expectancy used to be 7 years shorter in NYC than in

rural areas; after the systems were in place, it was three years longer!

But there also can be very bad, wasteful decisions: the corruption of

NY’s Tammany Hall in the 1860s led to huge fraud around water in NY; and

Detroit’s ill-conceived monorail system ended up being a complete waste of

money, due to the total lack of any prior cost-benefit analysis being

done. Glaeser is an ardent supporter

of public private partnerships (PPPs); and he is a

firm believer in the power of free markets.

He said, “If you build it, they will drive on it”—suggesting that it is

necessary to change people to use the streets differently. We need to be wary of the monumental level of

NIMBY-ism (“Not In My Back

Yard”; something to which my city planning friend Alex Garvin usually adds:

NOTE [“Not Over There, Either”] and BANANA [“Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere

Near Anything”]). As for climate change,

he pointed out that cities are not

the problem; high density living is a good thing ecologically.

Joan Clos summarized his

feelings by saying “I am a politician, not a scientist: I need to do things.”

KEYNOTE: Mohammed-Bagher Ghalibaf (three term Mayor of Teheran, below) gave a keynote

entitled, “Governing Teheran.”

He

said that in 2005, Teheran suffered from high levels of air pollution,

fragmented management style, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of meaningful

public participation in government. What

was missing, he said, was a social approach.

Subsequently, they have expanded their subway system from 2 to 7 lines,

tripling its capacity; they have introduced a BRT system; they have an

integrated, innovative, knowledge-based waste management system; and they have

significantly expanded their green space.

Teheran’s remaining challenges are poverty, child labor, panhandling,

addiction, slums, excessive immigration, and social injustice. As mayor, he is

building a social approach—focusing on decentralization and maximum citizen

participation: urban development should be based on public participation,

public education, and an awareness of the needs of low income people. The municipality must transform from service

provider to a social institution; a neighborhood management approach must lead

to citizen participation; the participation of vulnerable classes needs to be

insured in urban development plans; consumption patterns and social behaviors

need to be reformed to upgrade lifestyles. {Gee…it all sounded great…fabulous,

even. Just as one would want it to be;

and, if the truth be known, something I think might once have been possible to

work toward in that country, which, after all, has always had the largest, best

educated middle class in the Islamic world. (I always think about the fact of

Iran’s extraordinary current film community and realize the level of

sophistication of a major portion of that society, and conclude that it is the

country in that region that had by far the best chance of having a western

style society and government—democracy, even.) But Teheran,

in 2014 Iran... IDK…}

UBANIZING GOVERNMENT: DEVOLVING THE SATE. (Chair: Jagan Shah [Director, National

Institute of Urban Affairs] and Andy

Altman [Senior Visiting Fellow, LSE

Cities], pictured below)

Jagan Shah began by saying we need to understand urban governance

from a historical as well as political perspective.

He

said that Richard Sennett talked of a multiplicity of government, and Ed Glaeser had said the cities need government; it is people who are at the core of the

metropolitan phenomenon.

KC Sivaramakrishnan (Chair, Centre

for Policy Research) spoke on “A

Voice for Urban India: Decentralizing Governance.” He began by saying he

carries the burden of memories, of

the historical perspective—of politicians not wanting to move forward. Urban government is thought of as “lesser,”

and cities are under-represented in parliament.

India’s 74th Amendment has not helped bring about better

representation as it was designed to do; the base has been fragmented. Mayors in India continue to be ceremonial—and

are virtually always “one year wonders”; and moreover they are increasingly not

directly elected. The major loophole in

the 74th Amendment is 243Q: state governments are allowed not to set

up municipal bodies in industrial townships.

Do we want politically appointed officials to run our cities? He is suspicious of the 100 Smart Cities

initiative, supposedly designed to deliver better services; sees it as actually

a way to maximize privatization by creating a way to monetize land—and that is not smart. There must be political accountability. There is a problem of fractured thinking:

government and governance need to go together. Do we really want democracy—and

are we willing to pursue it? There does

not seem to be enough of an outcry on the part of the people—or any real push

for control.

Gerry Frug (Professor of Law,

Harvard University) spoke on “Deciding Who Decides.”

People

think that city governance means government needs to be more responsive to the

governed, The organization of city government is

always in the hands of central government: in the US and India, it is in the

hands of the states; in most of the world, it is in the hands of national

government. It is these central

governments that decide matters of revenue and what cities can do. The result of this central control is the

creation of endless bodies—government fragmented along specific functions. The answer does not lie in local authority;

every issue (land use, transportation, housing, the environment, poverty) is a

local, state, and national

issue. Also, every city is surrounded by

others; cities cannot decide their own futures: incompetence, corruption, etc.

Yet local democracy is vital for human freedom—people need to have

control over their own lives; it cannot be handled nationally. Both arguments are correct, and they conflict

with each other; both bottom-up and top-down control

are necessary. The question is how

cities can participate in the allocation of power. Gerry

discussed the situation in the US (as he did in detail in his most insightful

article by the same name in the conference Newspaper:

People

often think of city governance in terms of local democracy: the goal is to make

city officials more responsive to the local population. In the United States,

this certainly is one of the issues that needs

addressing. But it is not the whole story – indeed, it is less than half the

story. It fails to mention that the design of city governance is not in the

hands of local residents or city officials. It is the product of state law…

This dual

focus of the structure of city government – sometimes responsive to local will,

sometimes responsive to state policy – is a fundamental ingredient of city

governance in the United States. It cannot be overcome – and should not be

overcome – by choosing one perspective over the other. Local responsiveness is

sometimes undesirable, and so is state policy. Instead, the primary task of

city governance reform in the United States is to redesign this dual focus to

better align state policy with the exercise of decentralised

power.

The city

governance problem in the United States is that both positions just outlined –

for state power and for local power – are correct. Yet they contradict each

other. The governance problem, then, is to figure out how to deal with this

contradiction.

…the

better approach in the United States would be to shift the power to allocate

decision-making authority from the state to a new kind of regional institution.

What this

means is that the regional institution should be a forum for collective

decision-making by the region’s cities. Every city in the region should be

represented (with votes weighted by population), and the decisions they

collectively make about the allocation of power should be decisive. One should

note that this is not a call for city autonomy. No city, acting alone, will

have authority over an issue unless the cities collectively agree that it

should. In this way, the regional organisation can

help overcome the parochialism that now undermines efforts to decentralize

power. Neighbouring cities affected by any decentralised decision would be part of the decision-making

process: they can make sure the allocation of power takes their interests into

account. The key difference for city power in this proposal lies in the fact

that cities – if they work together – will be able to design the decentralized

system.

Naturally,

this notion of new regional agglomerations of power appeal to Gerry as the answer elsewhere in the

world, as well—although he is careful to maintain that he knows this directly

only in the US.

Andy asked: so, who

decides? We have to decide what we want—but who decides? KC you were part of crafting of the Amendment,

but you said that the attempt to empower city government has failed. But you also talked about weak demand, a lack

of meaningful desire on the part of the citizenry. So both the legislative attempt from the top

and the push from the bottom seem to be ineffective. Importantly: who is the “we”?

KC said that we have

not come to terms with the reality of urbanization: for a long time, we

accepted the rural; now we live in cities, with the reality of urbanization and

the effects of urbanization—including increased inequality and the feeling of

being a part of a meaningless process of urbanization.

Panel

Discussion.

Charles Correa (Architect, and my dear friend from

early in the Urban Age program) [As I said earlier, I call your attention to

the video of our friend Charles Correa,

which I suggest you watch to get a sense of the power and elegance of Charles

and his thinking. His brief talk begins at minute 31:30

of the panel available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=dloCPkws8i8&t=26m15s.]

Charles

said that we have democracy in our country, but not in our cities. In a model left over from the way the British

governed in colonial times, India’s cities are run by chief ministers and

cabinets, not elected by the people

whom they are governing. They make all

the crucial decisions. In his excellent

article, “Accountability and Governance,”

Charles wrote that

There are

two crucial aspects of urban governance that our cities desperately need…:

Accountability…and proactive governance.

Around

the world, more and more cities are being run by political leaders who are

directly elected by the people of that city. So they champion the interests of

the citizens - or they will not get re-elected. That is the essential mechanism

by which Democracy ensures the accountability of our political leaders. It’s as

simple as that.

To

install this system of accountability, we need not convert our cities into

independent city-states. …That is what

democracy is about: confrontation resolved through a process of negotiation.

This

unfortunately is not what happens in our Indian cities. Instead of this system

of tough negotiations, with each side trying to protect the interests of their

respective electorates, our Indian cities are run by a State Chief Minister who

is not elected by the citizens of that city – and who can therefore be

completely oblivious to their wishes. …Our Chief Minister has no accountability

whatsoever to the citizens of this city because we do not vote for his

re-election. In that sense, we have no democracy in our cities! What we have

instead is a carry-over from the British Raj, where the Governor of Bombay

Presidency had complete power over Bombay – as well as all the other cities

along the west coast, right up to Ahmedabad, Karachi and Quetta.

In recent

years, Delhi has become the one conspicuous exception. But even this is not

exactly true, because the Chief Minister of Delhi does not have jurisdiction

over several of the most important civic bodies and government departments

which constitute that city.

When

Arvind Kejriwal became CM, this conflict came vividly

into focus. He stood up for the city government of Delhi, against the larger

political context, i.e. the Central Government. There is nothing wrong in doing

that. In fact, it is an essential part of his job. And let’s not forget, it was

the confrontation between Ken Livingstone and Margaret Thatcher, with their

conflicting agendas, that re-energised

the city of London.

The other

crucial ingredient missing in our cities and towns is pro-active governance.

…That sense of urgency is totally missing in our urban governance – although

the problems facing Third World cities are among the most fast-changing and

lethal we know, and crucial to our very survival.

This is

of crucial importance when it comes to the staggering problem that lies at the

heart of the crisis that most Third World cities face, viz., the distress

migration from villages to towns and cities - with squatters on pavements and

other crevices all over the cities. This has invoked two diametrically opposed

attitudes. There are those that say: ‘Throw them out!’ and others that say:

‘No, they have the right to stay where they are’. Neither attitude helps.

Letting them stay where they are, living in bestial conditions, insults our own

human values. Throwing them out misses completely the underlying problem, viz: the dehumanising living

conditions and viciously skewed land-holding patterns that prevails

in our rural areas.

Europe

went through much the same process in the 18th and 19th centuries, when

millions of desperate Irish, Italians, Jews, Germans, English, decided to leave

– and for much the same reasons. But due to the colonial system operating at

that time, they could re-distribute themselves around the globe – an option not

open to Indians today. So for the rural migrant, arriving in Kolkata or Pune is

a substitute for a visa to Australia. That is the functional role that our

cities are playing in the development of our nation. What we have to do is find

ways to increase the absorptive capacity of this urban system.

[The] National

Commission on Urbanisation’s…Report identified

several strategies through which this could be done… For example, in order to

alleviate the pressure on our larger cities, the Commission identified 325

small urban settlements that are growing faster than the national average –

despite the lack of basic amenities, like sewerage, water supply or transport.

Most of these are mundi towns (i.e., market towns) – for instance, Erode in

Tamil Nadu, a town of 160,000 with no sewage system, but which has evolved into

the most important centre in India for reprocessing

textiles. A bustling town, full of maniacal energy, it has buyers from all over

the world, stepping over open drains. If the right decisions and investments

are made, towns like Erode could form the nucleus of new urban centres that would deflect migration away from our existing

cities – completely changing the dimensions of the daunting problems we face.

And there are more than 300 other towns like Erode. This is why we need

proactive urban governance – instead of the passive attitude which has now

become chronic.

We need a confrontation between who runs

our Bombay and who runs Maharashtra. That is the strength of other places.

We need to harness

the incredible proactive force of India’s cities. Our government is faced with

an enormous challenge—we have never seen such a huge change in human

history: the distressed migration, all

over the third world including India. In

the past, colonial systems allowed for these people to redistribute themselves

around the world; that is not open to us today. When someone shows up today in Bombay or

Kolkata or Pune, it is a substitute for a visa to Australia! Our responsibility is to increase the

absorptive capacity of our system. That

is the real question we should be discussing.

We need to have an

overview: the Indian people have an

incredible energy and drive; but we cannot just sit back and wait for squatters

to appear. I have never seen the kind of

overview of analysis of India’s cities like what Ricky presented today—which are growing at what speed and why. We have cities developing where people are

stepping over open sewers in their streets; this is not acceptable. The cities of India are part of our national

wealth: they generate the skills we need

to develop as a nation (doctors, lawyers, engineers, managers, nurses—all urban

skills); our cities are engines of economic development; and they are places of

hope—and, for the millions of wretched have-nots of India, perhaps their only

road to a better future. What we need is

proactive government.

In the final

analysis, India’s cities will decide the future of the nation.

Hilmar von Lojewski (Councilor for Urban Development, German

Association of Cities)

began by saying how

wonderful it was to hear Charles, an architect, being so politically

interested; he wished architects in Germany—at least some of them—would be so

interested. Self-government is

guaranteed by the German Constitution, but there are still three dimensions we

need to work actively on—the political, the financial, and the people. Long

history (207 years, since the declaration of Riga) of self-governance in German

cities; on the other hand, we know how fast decentralization can come (e.g., Indonesia). He said that the burden of finance follows

the burden of tasks to the local level is a principle of great importance. There is a high interest in local government

performing well, but there is not a well-developed interest in participation in

local elections. We need to mobilize

people to participate in public life and public discussions.

Andy: so, in India’s cities “the fit is not right “; and

Gerry said it was not right in the US, even when there are strong mayors…

Hilmar: ‘Robust concepts’ are needed for urban

democracy and resilience. There is a

misfit: finances and power in cities are not aligned.

Gerry: We have to consider who are the stakeholders? They tend

to be corporations and powerful groups.

It doesn’t do any good for cities to “be responsive” if they have no

power.

Vijai Kapoor (Lieutenant

Governor of Delhi, 1990 to 2004)

spoke about the fact that

there were two Amendments passed at about the same time: the 73rd (which primarily dealt

with rural areas) and 74th (which dealt with urban): why were the

loopholes left in it, and why was such liberal use made of them? Why were

powers not transferred from central government to local government? Delhi, by executive order, was exempted from

the Amendment. The other question is why

was the obvious intention of the Amendment to devolve control to local levels

not carried through to other laws? The desire to be looked after still

overwhelms the other drivers in the process.

In 1957 when Delhi was abolished as a state, there was only the Delhi

Development Act and the Delhi Municipal Corporation (no Delhi Assembly), all

power stayed vested in the central government; but after Delhi was given a

measure of self-governance in the early 90s, why were those powers not

transferred from the central government? Local legislators cannot amend a

pre-existing parliamentary law without the consent of the central

government. The answer is that these

Amendments were merely political posturing: there was no attempt meaningfully

to transfer any power. KC mentioned weak demand on the part of

the people. There is also a weak will on

the local level to levy taxes. Take the

issue of the property tax: why is it non-existent to 90% of the urban

population? Delhi raises only about 1,000 Crores a year that way. If it were strengthened as a tax base, that

would activate the demand for local devolution of control—strengthen the

resource base. If property tax revenues

were transferred to local government, there would be a change; but where will

the active demand for local control come from?

Central government will not let go of power unless something is created

on the demand side. How does one create

that interest? Delhi is metropolitan area—is it a question of Metropolitan

government? Unless some innovative

approaches are created, we are not going to get out of the stranglehold of

central authority.

Wolfgang Schmidt (State

Secretary, City of Hamburg) said that he was “working in

paradise”

Because

Hamburg was a City/State.

Perhaps this can serve as a model?

Hamburg is one of 16 federal states (like Berlin); and each state has

3-6 votes in the parliament. Hamburg,

with a population of 1.3 million, has 3 votes (out of the total 69); three of

the states have a total of 10 votes out of the 69; and the biggest state, with

a population of 8 million, has only 6 votes.

Meenakshi Lekhi (Member of the India Parliament) said

that bureaucracy in India was completely unresponsive. There is a problem with responsibility

without authority, and of accountability.

Delhi has three

municipal corporations: each is not in position to do what is needed. There is a big question of who controls the

funding.

Gerry: If you organize localities so that the finances are

their own, the poor areas without resources will go under; if the control of

finances is central, the central government will have all the authority.

Neither one is working very well; we have a structural problem about organizing

finance, not choosing between the two.

Charles: The whole Chinese miracle was fueled by

Hong Kong; Bombay could function the same way, if we managed things

correctly. The mindset of the government

has to change; there needs to be a sense of urgency. India’s situation is far more urgent than

more developed places like New York.

It’s not just accountability; it’s urgency.

KC: There is a crisis of jobs, growing population,

migration. People and institutions have

to come together. Is the Amendment a policy or a posture? What good is

knowledge if you can’t come together and do something? All the big issues are multi-governmental.

Wolfgang: Hamburg collects € 30 billion, but only

gets to keep € 9 billion. How much can we really control? It’s a crucial

problem.

Gerry: Waiting for people to demand a change in the structure

cannot happen.

Andy: “Growth is managing complexity that you don’t

simplify.” The speed of urbanization

creates an urgency to generate dialogue about proper form and fit.

DAY ONE – 14 NOVEMBER

FRIDAY

Afternoon Session

Inclusive Governance: Agency and Disadvantage. Co-Chairs: Jo Beall, Director, Education

and Society, British Council,

and Mukulika Banerjee, Associate Professor of Anthropology,

LSE.

Abhijit Banerjee (Professor

of Economics, MIT) spoke on “Understanding the Choices of the Urban Poor.”

We have a vibrant democracy in India, why

don’t we get better conditions for the poor?

Several answers are given; but I am going to examine the evidence based

mostly on surveys done on low income neighborhoods in Delhi that provide

answers quite different from the ones commonly proposed. People actually are

not moving about quickly: the average length of residency is 17 years. Complaints about slums: water, sewage, and

garbage are the main ones; electricity is not a problem. Slum dwellers vote at the rate of 86%; they do participate. Politicians get money to spend on projects;

what do they spend it on—roads. Roads are not

a concern in slums. These people attend rallies, they approach public officials—much more than

middle class people do. Political

incentive is broken, but not because people don’t care or are in conflict. People do get faulty information—particularly

about the people who represent them.

Politicians are totally unresponsive to the real concerns of

people. The real problem is that

politicians assume they will not be re-elected, so they do not care. The political parties just move them to

another area the next time.

Sue Parnell (Professor,

African Centre for Cities) spoke on

the topic, “Governance Needs Government:

The Case of African Cities.”

Even back

in 1941, Nairobi was run for a particular constituency, and its governance

regime was basically imported. 70 years

later, we still know a great deal about Nairobi’s government: many aspects of the governance arrangements don’t work very

well: the revenue streams don’t manage to meet everybody; the legal code is

inappropriate both at the top and the bottom; the city is not working; and we

wouldn’t choose these particular forms of governance and government

going forward. We don’t talk about government,

because: 1) neo-liberalism and the reduction of state power relative to

corporate and financial forces; 2) poor state performance, governments lack

legitimacy, particularly locally; and 3) recent push for participatory

inclusion of non-state actors in urban management. In the context of this moment of city

building in the African context, we need to utilize the power of

government. Central governments have

been essentially anti-urban, or just haven’t known what to do about the

problems of cities. Local governments

are weak and lack jurisdiction over the majority of their population; and they

have to compete with powerful institutions like banks, gangs, or central

governments; and municipalities lack revenues.

The question of the state is back on the political agenda, so it makes

this an important moment. There are some things only the state can do. Reinstating the state in the process puts the